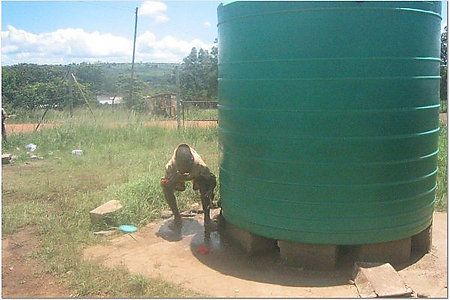

Here’s some info I got from Swaziland before the tank was installed.

This story came form Sister Maureen.

[i]Tiny Philiswa Maziya is a patient on the Pediatric Ward at Good Shepherd Hospital. Philiswa was born 3 months ago weighing a little over seven pounds. Since that time both her parent have died of AIDS and she has been chronically ill. A loving and attentive Gogo (grandmother) now cares for her, a not uncommon experience in a country where 56% of women in the 25-29 year age group are HIV+. Gogo Maziya and her family are part of the 77% rural based population in Swaziland depending on rivers and unprotected wells as the main source of household water, the cause of Philiswa’s chronic and increasingly life-threatening illness.

Because breast milk is not available to her, Philiswa has been fed from unsterilized bottles, using milk powder, which has been over diluted with unsafe water. She has had diarrhea for many days. On Feb.13 she is admitted with severe malnutrition, wasting and dehydration, weighing 4.8 pounds, a significant drop from her birth weight. Children under four years of age must have a caretaker with them at all times, so Gogo Maziya must now leave the rest of the family to attend to Philiswa in the hospital.

An IV drip is inserted to replace needed fluids, and because the baby is so weak that she cannot feed adequately on her own, a feeding tube is placed. Gogo Maziya learns to measure the milk mixture into a clean cup and dilute it with boiled water. Using a clean syringe she carefully inserts the milk with added micronutrients through the feeding tube in the hopes of coaxing this little one back to health. Gogo has learned to do this from Dr. Joyce Mareverwa, a pediatrician from Zimbabwe. Before Dr. Joyce came, GSH had no pediatrician. Since her arrival she has filled the pediatric ward with critically ill children – TB, malaria, HIV/AIDS, wasting and malnutrition. Because she is African herself, Dr… Joyce knows well these diseases. She has gained the affection of her young patients and the confidence of their caretakers. Dr. Joyce nurtures and nourishes many of these children back to life with her heart as much as with her medical knowledge. Now she turns her attention to Philiswa and the difficult work of saving her life

In Swaziland, only 33% of the rural population has access to a clean water supply. This lack of potable water is the chief cause of the high rate of infant mortality in the country from diarrhea, malnutrition and infectious diseases. Gogo Maziya and her family are part of this statistic. They live in a homestead in the Makehewu Community, an area not far from the hospital. There are over 800 households there, each family living in a one room, thatched roof house, without electricity or running water. There is only one water source for the community, which must serve them for bathing, cooking, drinking, laundry and crop irrigation. Women and girls spend an inordinate amount of time fetching water, often walking 3-5 miles, collecting it in large containers, which are then transported home in wheelbarrows or carried on their heads. It is from this water source that Philiswa was fed

Every year 1.8 million people die from diarrheal diseases, 90% of them children under the age of 5. I begin to worry for Philiswa. She has done well the first 5 days after admission, raising her weight from 2.2 to 2.8 kilograms. On Feb. 19, day 6 of admission, however, she has started having diarrhea again and has begun to lose weight. Despite the feeding and medication, the diarrhea continues. The next day, Feb. 21, I am shocked at the rapid change in her little body. . She is now severely dehydrated, clearly in distress. The soft spot on the top of her head is sunken in from lack of fluid, and her little heart is racing madly in an attempt to meet the demands of her stressed body. Gogo Maziya does her best to comfort Philiswa, but she too is feeling the urgency of the situation and her concern is evident.

On Feb. 22, as I make my daily visit, I see Gogo gently rocking the fragile little body in her arms. The feeding tube has been removed from her nose and the IV drip from her tiny arm. For the first time she looks like just a baby. And I realize that even Dr. Joyce, with her medical magic and caring heart, could not keep Philiswa from becoming one of the 1.8 million lost to this preventable disease. I have read that it would take the equivalent of 1% of the world’s military expenditure to provide safe water and decent sanitation facilities for all human beings. How do we measure a life?

I sit on the bed with Gogo Maziya for a while, not saying much, our shoulders touching. She asks me if she can have some of the photos I’ve taken of Philiswa, and I say yes, I will send them to her. Her grief is deep but restrained. She is a strong woman. She has buried her children; now she will bury her grandchildren. I look at the still, small body, still swathed in blankets and words of Isaiah, which I happened upon, come to mind:

In my pastures the poor shall eat

and the needy lie down in safety.

Rest peacefully, Philiswa.

You are safe now, little one. You are safe.[/i]

Philiswa on admission

Philiswa with Gogo in the Peds Ward

Dr. Joyce exams Philiswa

Philiswa the day before she died

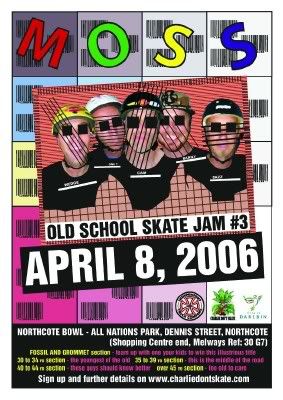

MOSS

MOSS